Conversation between Xavier Fumat, Gemini G.E.L. Master Printer, and Chris Santa Maria, Director of Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl

September 26, 2024

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Chris Santa Maria: Thank you for being here tonight. I want to start by opening this conversation with a few acknowledgments. This exhibition wouldn't have been possible without one of the most important and fundamental aspects of Gemini G.E.L.'s long-standing principles, and it's something that Gemini’s late co-founder/owner Sidney B. Felsen always hammered home when it came to discussing the dynamic that Gemini nourished between its artists and printmakers.

And that's collaboration.

Clara Serra and Trina McKeever, thank you so much for your endless support and guidance throughout the planning of this show, and to Joni for your fearless leadership and assistance, no matter how big or small the challenge. To my beloved colleague Elizabeth Fodde-Reguer, so smart and beautiful. And our brilliant young assistant Henry Wahlenmayer, who is now at the Brooklyn Museum.

Sidney left us just three months after Richard Serra passed away, and it really feels like the end of an era in many respects, both in terms of Gemini as a family, and within the tradition of printmaking and its role in the history of art. The legacy of Gemini will always be in the collective hands of its artists, printers, curators, sales and administrative staff. And of course, all the collectors and institutions that have supported Gemini in its nearly 60 years of existence. Here in our New York gallery, I'm proud to say that we're always surrounded by some of the most incredible prints and editions that I personally and professionally believe have ever been made by any artist or workshop. And this exhibition is one of many we've had the privilege of mounting that we think demonstrates this point. Gemini has been very fortunate to become such a legendary institution since it was started in 1966 by Stanley Grinstein, Ken Tyler, and Sidney. So it is an honor and a privilege to be here with you today in conversation with a living legend himself, Gemini G.E.L. Master Printer Xavier Fumat.

Xavier Fumat: Where's that vodka? [laughs]

CSM: Oh we’ll get there [laughs] but before we do, there are a few questions that I have always wanted to ask you Xavier, and I'm sure there are some things that our audience wants to hear about in terms of Richard Serra's work ethos, what he was like at Gemini when you guys were collaborating on different projects. I really want to delve into some of the stuff that deals with process, how some of these etchings we’re surrounded by were made, and how some of these massive large-scale editions were created. But I also want to start all the way at the beginning. Like, how did you get paired up with Richard Serra 25 years ago. What was that experience like for you?

XF: Well I did an internship in the summer of ‘98 at Gemini and I was working with Matt Jackson on some Richard Serra projects. I then went back to school and got hired full-time afterwards. I had already worked on some Ellsworth Kelly projects and a few other prints, and then Matt left.

Jim Reid was our project manager and he asked all the printers, “Who wants to work with Richard?” and nobody raised their hands [laughs]. And I was like, I want this, I’ll do it. So I volunteered and thought, you know, how hard could it be?! [more laughs]

CSM: And how hard was it?

XF: It could be very hard!

CSM: Sidney would sometimes describe Richard Serra in the workshop as a steam locomotive. You just had to get out of his way. Is that how you felt, as well?

XF: That’s definitely one way to describe what Richard was like in the shop. Like, you would just stand there and so much was going on around you, right? It was insane! Everything moved so fast. That was Richard.

CSM: So before a project would start, would he call you up and say I need this many sheets of this kind of paper at such and such scale, have it all ready for me? Because when I study some of the photos that Sidney had taken over the years, it's like the whole workshop is covered with cardboard and brown paper from the ground up, to protect Gemini from the black oil that was about to be unleashed.

XF: In the beginning, obviously he was working on pieces that were 48 by 72 inches, I believe copper plates that he was making drawings directly onto. So, when I started there was already something there that allowed me to understand and expect what he might want to do. He would never send me anything ahead of time. It was always a situation where he would just come in with a different idea. You had to have an open mind about whatever he wanted to do. It actually allowed me to not stress out about it, or think, what the hell does he want to do now?

CSM: How did your role as his master printer evolve and change over time? Like, did he teach you things about printmaking? Did you teach him? Was there a symbiotic dialogue about the possibilities of the medium?

XF: He once told me a story about when he was a student at UC Santa Barbara and his plate ripped up the blankets on the press and the printmaking professor kicked him out of the class. You didn’t have to have a super deep understanding of the actual process, because he knew what he could do. Understanding what he was interested in as an artist allowed me to actually make what he was looking for.

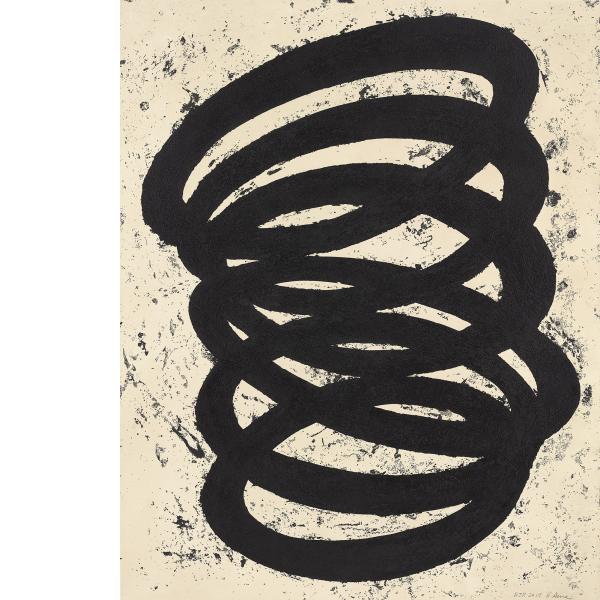

CSM: These copper plates that I’ve seen at Gemini, they're so deeply etched. It's almost like the acid is about to cut through the backend of it.

XF: It did sometimes!

CSM: Did you have to discard the plate and start over?

XF: No way, we used it. You just ink it up and put it through the press.

CSM: But wouldn’t the ink press out underneath?

XF: Some of the plates actually had to be adhered to a sheet of aluminum because they were so fragile from the etch, just moving them around could break them. One of the things with Richard was there was no such thing as re-making a plate. It was one and done. It either works or it doesn't. And I think that is the reason why I absolutely fell in love with working with Richard. So I talked to Sidney and said, I think my experience and capability in making prints would be best suited if I only work with Richard. And Sidney said, “Okay”.

CSM: Yeah I would find it hard to believe that you could be working with Richard and then shift gears to something clean like an Ellsworth Kelly litho.

XF: In the beginning, it wasn’t the easiest thing to do. There was a time when we were printing Serra’s and then Jim Reid would be printing Kellys and he had to actually build a hut-like structure around the press so Richard's mess wouldn’t get onto the Kellys. It looked so weird and funny. But at Gemini, you do whatever needs to be done to achieve what you're actually attempting to make.

CSM: Sidney would always say that, too. Never say ‘no’ to an artist. You do everything you can to try and figure out what needs to be done for a particular project. But which prints, in your mind, were the absolute most difficult to achieve? Was there ever a challenge you feared may not work out?

XF: Yeah, I would say that about the largest prints. At one point, copper plates only came in 48 inches wide by 10 feet, and Richard wanted to work on something wider. One of the things Sidney always said was, “Do whatever Richard wants.”

And so I called this place in Texas that made copper sheets and they built one for us that was 60 inches wide by 10 feet. When they arrived at Gemini you would just look at the sheets and say, oh crap. Like, how am I going to do anything with this? And they weren’t polished, either. So my team spent days and days sanding all the way down to getting it to polish. So those prints were the most difficult simply because they were way bigger. Bigger than anything I had done before. I was just like, I hope I can do this. I hope I don't fail.

CSM: Are the Rift etchings the largest that Gemini ever published?

XF: I mean, they have to be. They were 60 by 94 inches.

CSM: And that's just one panel, right? Some of them had two or even three panels that measured 94 x 180 inches overall. How the hell do you etch something that large? Because traditionally you take a copper plate, put it in a tray filled with acid, and agitate it back and forth on a tabletop.

XF: We didn't have a tank that was big enough so I had to look into having something custom built, and we actually built three tanks because the plates kept getting bigger and bigger until we reached 94 inches. The reason that 94 inches was the limit was because the biggest press we had couldn’t print anything more than 94 inches. When you start getting into that size, you cannot lift the plate from the ferric chloride on a horizontal surface because the liquid is probably 3 or 4 times the weight of water. So in that situation, we decided, well, why don't we etch it vertically? So we built the tank, and by the way, our etching tank holds 750 gallons of ferric chloride. You know, most etching tanks hold 5 gallons. But then we realized the ceiling was too low, we couldn’t lift the plate high enough. So we ended up cutting open the ceiling in our Frank Gehry building to get it in there.

CSM: That is insane!

XF: Thank you. Sidney would just say do whatever he wants. Whatever he needs.

CSM: This is also one of the things that I think about with regards to Serra’s sculptures. He was pushing entire industries to quite literally bend to his will, to create larger, more complex, more sophisticated artworks. It’s crazy and beautiful at the same time.

XF: Yeah, I mean, that's what I thought. But there we were, cutting a hole into a Frank Gehry building.

CSM: Richard must’ve loved that.

XF: Yeah, I think he really enjoyed it but then I was like, oh, man, I hope we can fix this! [laughs]

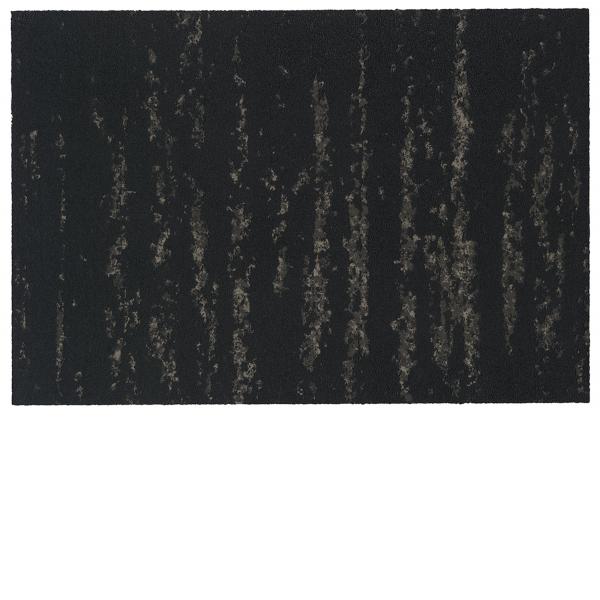

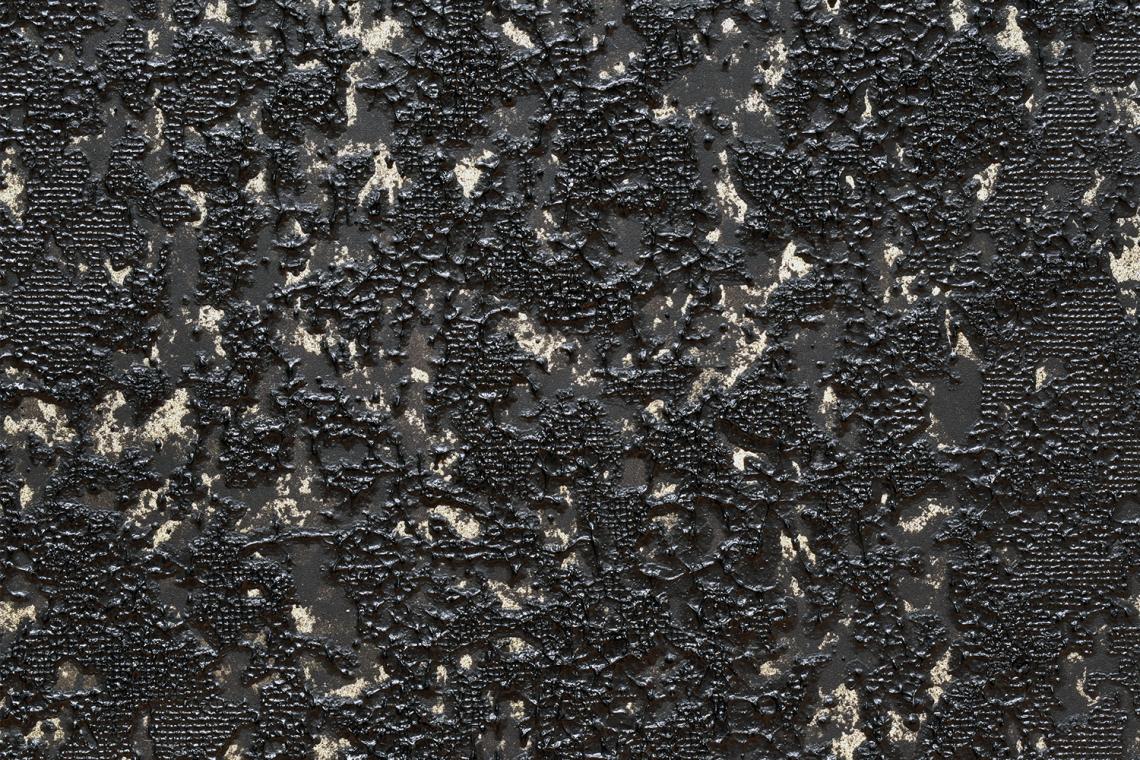

CSM: I want to shift a little bit and talk about some of the later works. The editions that involve oil stick and silica, literal grains of sand and rocks mixed with etching ink to be rolled onto the paper with an etching brayer. Technically speaking, these aren’t prints because you’re not transferring an image from one surface to the other.

XF: Exactly. There’s no matrix.

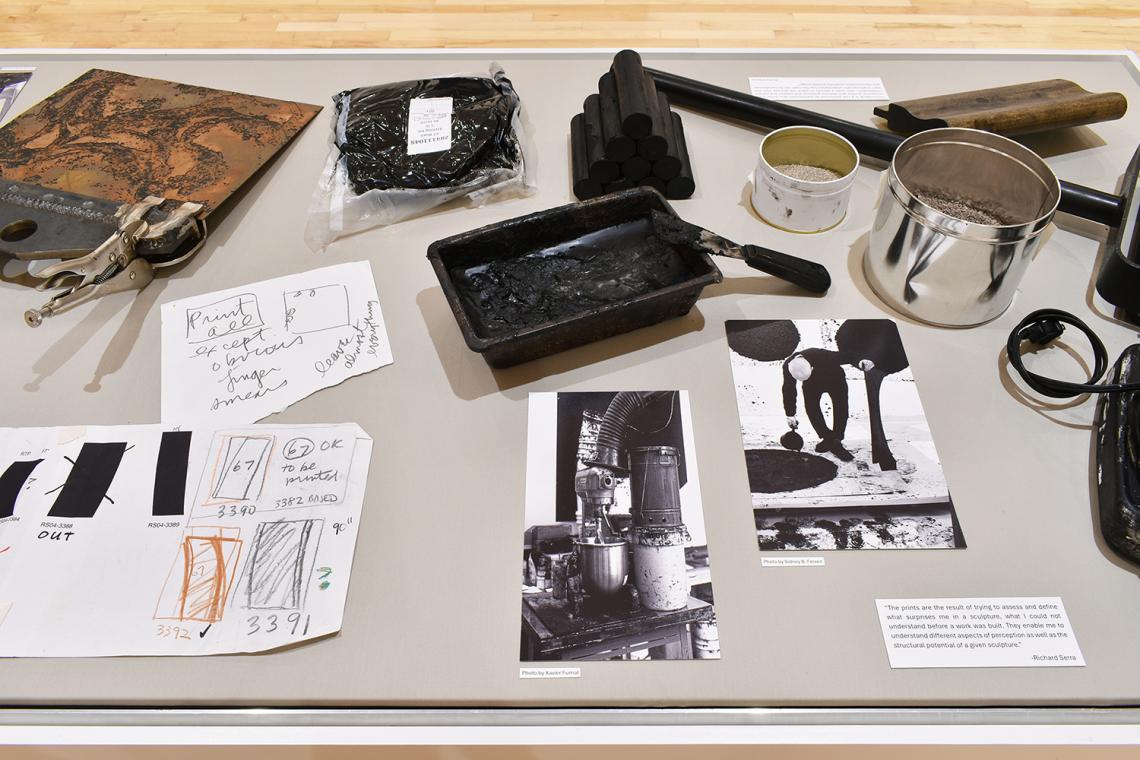

CSM: I remember visiting Gemini about 10 years ago and noticing all the meat grinders and cake batter mixers, wondering why a bunch of industrial restaurant supplies were in the etching workshop.

XF: Okay so first off, you gotta understand that Richard took me to Gagosian Gallery to look at his drawings, which were the Rifts, and he says, “I want you to make something like this. This is the kind of surface I want in the editions.” And for years Richard would ask me, “Why can't you add sand to the etching ink so it’ll be crunchy?” And well, if you've ever done any printmaking, you know that would scratch the hell out of the surface of the plate, which means it would be unusable. But that question had always stood out in my mind, and when I saw that show with him, I thought, wait a minute…maybe we can actually mix something in the ink. And then I remembered some coursework we took at Gemini about managing hazardous waste spills, and the guys teaching it came in with this material that absorbs oil. They were using it for car crashes on the freeways and I was like, well, let's use that!

So we started out by grinding the oil stick with a little hand grinder and we got through about three boxes and were like, oh, hell no. This is not going to work. So then we thought, well, what about a meat grinder, right? So we bought one and it worked, but maybe a month later it broke down and crashed. Same thing with the store-bought blender. All this stuff kept breaking down so we reached out to Nancy Silverton and she suggested that we get something more industrial, and that’s when we got an old school Hobart. The gear mechanism on that was super strong and we used it for many, many years. And I think maybe about three or four years ago, it finally broke. And so we ended up buying a newer one, but I still got the old one fixed because that thing is so cool. Think 1950’s mechanical things, you know, it had that look that, a very beautiful design. I'm glad we fixed it.

CSM: That’s so great.

XF: Yeah.

CSM: Let's consider some of Richard’s later editions. He started using Paintstik in the 80’s but at that point he was rubbing it through a silkscreen. But something like this piece behind us, which is from the Casablanca series in 2019, and over here are the Hitchcocks, which are the last editions that Serra created at Gemini before he passed away. The way the texture is built up on the surface is even more intense than anything he had ever done at Gemini.

When Hal Foster spoke at Serra’s memorial at MoMA last night, he talked about several conversations he had with Serra up until the end, where he asked him, “Are you conscious that you are making late work? That you are an artist making his last works?” And of course Serra was conscious of the fact that he wasn’t going to live forever, but when you and he were working together, did you guys ever talk about this kind of existential stuff?

XF: Look, I thought Richard was going to outlive me! He just kept going and going, one project after another. It felt like he was never going die. It was just non-stop BOOM BOOM BOOM and then again, BOOM! BOOM! BOOM! Everything was overwhelming with him, but always doable.

CSM: I do want to turn to the audience for some questions because I feel like y’all could probably bring up some topics that I'm not thinking about. But before I do, I want to relay a question from Jennifer Farrell. She's the curator of prints and drawings at the Metropolitan Museum and she wondered if there was any project that was an abject failure, something that simply didn't work, and why?

XF: Well, we did a project called Composites that started out as a failure but ended up being really successful. In the beginning, Richard was like, “Okay, this is good” and then we got through some more proofs and he called me and said, “You know, I don't like this. I don't like this at all. This is not what I want.” So they got canceled.

But then, about half a year to three-quarters of a year later, he told me, “I really want to do this project. I want to get the feel of what my drawings look like.” So we did some more...and it didn't work. And so he was like, really let down. And of course, I was like, oh my God. Like, I've never failed to make something happen for Richard on my side of things, and you don’t just leave it. Sometime later he called me and said, “You know, I really, really want these.” And I thought, okay, everything we try hasn’t worked, so let's just throw printmaking out the window, let's make these images that Richard wants. So we ended up taking his drawings, I think he sent us 20 drawings and I was able to look closely at them, really study them. I photographed one and used that image as the background etching. The plate was based on the surface area.

CSM: Like a pattern?

XF: Yeah, just the pattern. Because the thing about the Composite drawings was this feeling that you were looking through smoke. You were like in a forest with fog and you can see these forms by looking in and out. And we were not getting that effect in the prints. Richard didn't always express exactly what he wanted me to do. It was like, you should already know, and so then I thought, well, why not just smear the oil bar based on this drawing through a silkscreen with a gigantic open square. And he loved it!

CSM: We have one of these Composites hanging in our show right now, and I’ll never forget when we installed all twenty-two of them in 2019. We were unwrapping all the frames and I was like, wait, each of these has an entirely different texture from one to another, edge to edge. It really is like you’re looking out through a forest in the middle of the night. They’re amazing prints!

Then we heard that Richard wanted to come and see the show when Joni and Sidney were in town. We were all waiting patiently in the gallery for Richard and Clara to show up and then the elevator opens and he beelines it to the smallest piece hanging near my desk. There's only one small print in the entire series, the size of a sheet of office paper, and he walks straight up to it and puts his fist on the wall and leans in and says, “These are some good fucking prints!” And I was like, “Oh my God.” [laughs]

So then I called you and was like, “Dude, he loves them. He walked around the entire gallery and genuinely looked at every single one of them, like an interrogation of his own work and your attempts to capture it through printmaking.”

I was witnessing the end of this process between you and him, and it was so great.

XF: When we were making those prints, the screens had to be cleaned every three or four runs because they started to spread too much. We would mess with how fast the paper would get pulled away from it, because they would stick to the screen depending on the speed. It was a free-for-all.

CSM: Sounds playful!

XF: Yeah, it was, and they turned out to be amazing prints. Amazing prints.

CSM: Unfortunately, they don't photograph very well but when you look at them in person, especially in context with the entire body of work, to me, it’s one of my favorite projects at Gemini because of how varied the surfaces are and how difficult it was for your team to make them.

Does anyone have any questions?

Annabel Keenan: You worked with Richard for what, 20? 25 years?

XF: Yeah.

AK: I was looking at the vitrine with all the hand-written notes in it, and to me, they don’t really make a lot of sense. You had to translate them, what was that like?

XF: Good question. Richard would send something to me and sometimes he would include these notes, but normally he would only call me and start speaking at like 100 miles an hour and I'm just there trying to write down letters and word after word. And I'd be like, I don't know what he's saying but I'll figure it out. Whenever I sent him back early proofs he would put notes on the print. “I need this taken out” or “I need you to do this” or whatever. But it was always such minimal information and he expected me to absolutely know and understand.

It was really hard in the beginning and I thought I was gonna get fired. And then after a while, I kind of just understood it all. I figured out the direction he was going in and it got easier to not write things down and just go with it.

I think what he enjoyed about working with me was the understanding of what to do without actually saying what he wanted to do. I don't know how that happened, but things clicked so quickly that I could totally anticipate his thoughts. He didn't have to explain anything, and Richard was not a person of little words. He liked how I could decipher the minimal information that he was giving me.

Audience: What is it like for you to see all these prints up on the wall now?

XF: It’s surreal. I look at the work and it feels like somebody else made these. I have the memories and the experience of doing it but I rarely have the opportunity to see them in a gallery or in someone's home, so they feel a little foreign and yet, I’m like, wow, this is really amazing. I have to remind myself that I did this for so many years.

You know, working at Gemini, we don't really get to see the framed pieces except when we have an opening reception. But for the whole duration of editioning, one print on top of another print, they have a completely different value. It's something you're making, you’re always touching and moving it, but when you actually see them like this, in a grandiose space, it’s something I can’t touch anymore. They demand a different kind of attention and respect. It’s very different from the experience of being at Gemini and seeing them there.

So that's the difference, right? It's like it was something you would handle. You can touch. You can, like, move and all of a sudden they're in this grandiose space that demands attention. And respect. So, a very, very different experience from being at Gemini and actually seeing them here.

Audience: Could you describe what Richard was like in a more personal way?

XF: You know, it's complex. Richard was so many different things that I couldn't just pinpoint him down on one thing. But he was a machine that didn't stop and I think that's why I chose to only work with him. I've often compared him to a boxer, like Joe Frazier. He wasn't necessarily the greatest boxer, but he was a machine that came at you. It didn't matter what you did. He just came at you and came at you and you just finally had to start backing away. That was Richard for me. It was so impressive.

But there were a lot of tender moments, too. Especially when he actually really liked something.

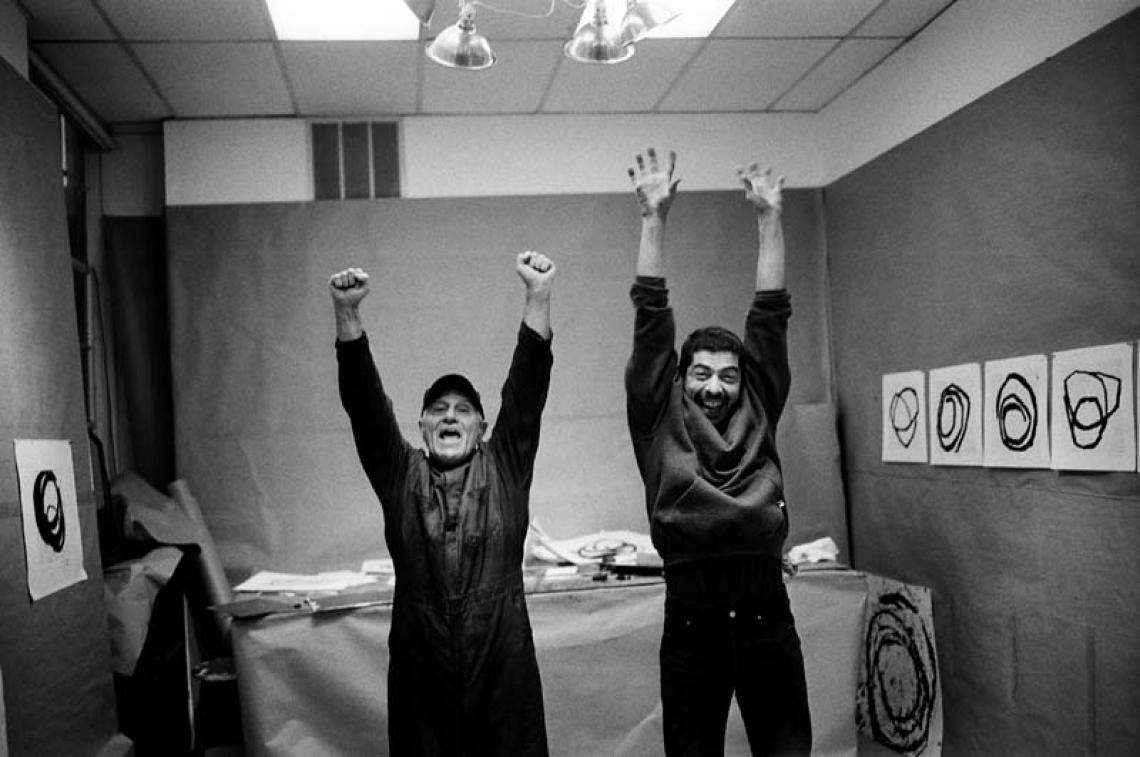

CSM: I noticed in Sidney’s photos, you can really see him smiling and laughing at Gemini. It seemed like he was truly happy there.

XF: It’s true. You could really tell when he thought something was good because he began with this grin and then he would tell you, “This is good. This is really good.” And he would just keep repeating it, repeating it, repeating it. And I was like, I got it, Richard! I got it! But he would keep repeating it. And of course there were other moments that were very personal to me, where he didn't have to say anything and I just knew.

CSM: When he got older, did he soften up?

XF: I think he was always Joe Frazier. I think he was always the machine. Right, Trina? [Trina nods affirmatively from the audience].

That never changed. It was like, you better be ready to fight and fight till the end.

One time we were working on some of the Torqued Ellipses and we were melting the oil bars and then he would grab a tool and I would have to hold the template and he would dip it down and just start going out it with all this splashing around. And this stuff is just getting in my hands and it's actually burning my skin!

CSM: Jesus, man!

XF: I was like, oh my God, what the hell? And it was getting on him too but he wasn't complaining. So it was like, I'm gonna have to take this.

And that was Richard. I think that's what I loved about him. He was so real and he allowed me to be real. I could try whatever he wanted, it didn't matter what it was. One time Richard asked me if you could print an etching over a litho. Physically, you can. But technically you cannot because you have to soak the paper to print an etching. It expands. And so, knowing this, I told him no, you can't, you just can't. And then he asked someone else, can you do this? And they just said, ohh, yeah, absolutely. And that’s when he turned to me and said, “Don't you ever fucking tell me you can't do something until you've tried it.” And from that point on I was like, okay, I got it. I got it.

CSM: But wait, you tried it and then what? It didn't work, right?

XF: It didn’t! The registration was off but I thought…nobody will see it, right? Because it blends. Like, as a printmaker, you go, this is interesting. It doesn't quite register here but you'd have to be somebody who’s really into printmaking to be able to notice it.

But yeah. I was correct. I was right. [laughs]

But he taught me a valuable lesson, which was so true. When we started doing the big giant prints I was like, of course I can do this. Yeah, it's like, why not? Figure it out as you go! That's what I learned from Richard. Don't ever say no until you actually can't do it.

CSM: This is an interesting point, as it relates to a conversation I had with Allison Smith at Gagosian Gallery about how she would plan the logistics of moving his steel sculptures from Finkl Forge Germany all the way to New York City. And when the works became too heavy even for George Washington Bridge, she discovered that a barge could actually move them from Jersey straight to the Chelsea docks near the gallery. When she told Richard about this, she was like, oh my god, what have I done? He’s going to go bigger and heavier!

XF: Yeah, be careful what you wish for when it comes to Richard! He would always ask me, “Could you do a bigger print for me?” And I was like, yeah sure, why not. And they would get wider and taller and it just happened, we succeeded. It was such an experience. I mean, Sidney was an amazing person because I think he allowed everyone to not freak out or be intimidated by something. You know, he would put things in my hands, he would give you the responsibility. You can do it! And that combination with Richard, always pushing ahead, more and more, it made it so easy for me to feel comfortable and confident that I could do this. It’s no big deal. I think about it now and I'm like, wow, that was some crazy stuff. Like, I would never suggest doing any of that stuff now. [laughs] No way am I taking those chances.

But yeah, these two amazing people that I lost within a very short time, they literally changed my life, to be a better person in a better place. And now they're gone and it's like the memories are here and they’re constant. It’s a great thing.

CSM: That’s beautiful, man. This was really nice. Thanks for being here tonight.

XF: You’re welcome.